|

|

|

|

#1

|

||||

|

||||

|

Randy Bass

There have been three waves of American players going to play ball in Japan. Or, better, there have been two wavelets with lots of ripples and then an actual wave. When the first professional league was formed, a handful of American players headed overseas. Some were children of Japanese immigrants, including the greatest of them, Tadashi Wakabayashi. Others were not. For example, Harris McGalliard (AKA Bucky Harris) was a part-time PCL player and briefly a Pirate farmhand who, seeking a chance to actually make a living playing baseball, headed to Japan in 1936. He played six seasons (three years, in the early days they played two seasons per year) in Japan, winning the MVP award in the fall of 1937. During the war, since he spoke Japanese, Harris was employed interrogating prisoners in the Philippines. Reportedly one of them was a former professional baseball player, and Harris spent much of the rest of the interrogation answering questions from his former colleague. Another American, Herb North, recorded the first win in Japanese professional baseball history, pitching in relief for the Nagoya Golden Dolphins over Dai Tokyo. His Japanese career lasted one season, then he returned to Hawaii to play amateur ball. That Dai Tokyo team featured another American, Jimmy Bonner, who grew up in Louisiana and played for independent Black teams in California before being recruited to play in Japan. His career there lasted only nine and two-thirds innings, but he integrated Japanese baseball more than a decade before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in America. There were only a few Americans playing in Japan in the thirties, and the war put an end to any hope of bringing in more. Wakabayashi renounced his American citizenship and stayed in Japan. Everyone else had gone home by that point, and no one else went over. Famously, Wally Yonamine was the first American to head to Japan after the war. Several Black ball players followed him, and gradually a handful of white players as well. They trickled in through the next few decades, including a few prominent players like Larry Doby and Don Newcomb. Most played in Japan only very briefly. The real wave began in the 1980s, or perhaps late 1970s, and has only picked up steam (if you’ll allow a very tortured mixed metaphor) since then. When people now think about American players in Japan, it’s this wave that they are thinking about. These players are (were? has this changed?) called “helpers,” indicating a popular perception that they are valuable adjuncts to a team, but not really members of it. Although there have been exceptions, most players from this wave were good minor leaguers who never really got a chance in the big leagues, or poor big leaguers, who couldn’t cut it. Mostly they have had relatively short careers; in part because the cultural transition is difficult (not just US-culture to Japanese-culture, but perhaps even more significantly US-baseball-culture to Japanese-baseball-culture), but also in part because they generally only leave for Japan after finding that their American careers have stalled-out. Now that we’re 500 words into a post about Randy Bass, it’s time to mention Randy Bass. The Twins took him out of Lawton (OK) high school in the seventh round of the draft, and he proceeded to crush the ball. He slugged over 500 with an on-base percentage in the mid 400s as a teenager in the low minors. He skipped AA and was sent to the PCL as a 21-year-old. Bass’ first go-round in the PCL was mediocre. The stars of the team were a former Seattle Pilot named Danny Walton, and a young Lyman Bostock, who spent most of the season in Minneapolis. Bass was young for the league, however, and was asked to repeat it twice. In 1976 his on-base percentage returned to above-400 levels, but his slugging was unexceptional for a player limited to first base. The next year, his third in Tacoma, Bass blossomed, finishing second on the team in both on-base percentage and slugging percentage. (Or maybe first place, depending on how you count. In both categories Willie Northwood finished ahead of him, but Northwood appeared in only 53 games for Tacoma, and hit anomalously well.) Anyway, you’d think that would be enough for Bass to get a shot, but it wasn’t. Not really. The Twins gave him a couple weeks in the show and then sold him to the Royals, who relegated him to AAA again in 1978. For his fourth year there. Now, to some extent this is understandable. The Twins had Rod Carew playing first base, and no matter how well Bass was hitting in the PCL, he’s not supplanting Rod Carew. But this was 1977, there was a DH slot to fill. The 77 Twins filled their DH slot mostly with a platoon consisting of Craig Kusick and Rich Chiles. Cusick was 28 and had hit well in limited playing time for the past three seasons. Bass was younger and had more room for growth, but in 1977 it was reasonable to think that one day Randy Bass might grow into being Craig Kusick. And, well, the Twins already had one of those. Chiles’ role on the team is harder to understand. He played nearly half of his career MLB games in 1977, and didn’t hit particularly well. The previous year he’d be an adequate AAA player, but he was older and no better than Bass. Cusick did have a nasty platoon split, so he needed a lefty bat to share the position with him. The Twins chose Chiles, but I don’t see any reason to expect better performance, in 1977, from Chiles than from Bass. Anyhow, the Royals sent a 24 year old Randy Bass to cool his heels in Omaha. He was the best player on the minor league team, and it earned him two at bats with the Royals. Their main first baseman that season was Pete LaCock, who put up a 110 OPS+ in 1978, but still hit all of five home runs and was below replacement level for his career. (The DH slot was more competently filled by Hal McRae.) I suppose the Royals figured that LaCock is 26, a good age for a breakout, and putting up production that, if below average, is at least not terrible. They opted to stick with him for another year and sold Bass to the Expos. The story was basically the same in Montreal. Playing in Denver he hit 333/454/660. These numbers are, of course, inflated by the fact that he was playing on the top of a mountain, but he was still the best player on the team. The Expos rewarded him by, I’m not making this up, giving him one at bat on the major league team. He was blocked by an elderly Tony Perez, who, unlike LaCock, at least had a history of good performance. This being the National League, they didn’t have a DH spot at which to hide him either. (And in any case they had Rusty Staub in the fold. Presumably he’d have DH’d if it had been an option.) Even so, they couldn’t even find any pinch hitting at bats for him. The 1980 season, in what must have been a tiring routine for Bass, was more of the same. He and a very young Tim Raines were the best offensive players on the Denver team. Perez had moved on, and in 1980 the Expos were playing Bass’ fellow future-JPBL-star Warren Cromartie at first base. Cromartie was an established big leaguer, and even had one good major league season under his belt, so there was no place for Bass to play. In September, Bass was named as the player-to-be-named-later in an earlier deal, and sent to San Diego, where he finally got a chance to play major league baseball, if only for a few weeks. He got into 19 games, and put up a 286/386/510 line. That’s good! It was good enough to get him his only real break in major league baseball. In 1981 he played 69 games for the Padres, but, for the first time in his career, he didn’t hit well. In his only extended period of major league play, Bass hit 210/293/313 and was released. The following season he was again the best hitter on his AAA team (again in Denver, although this time as a Rangers affiliate). He played poorly for a couple weeks in Texas, was waived, played poorly for another couple weeks in a second go-round in San Diego, and that was that for the 1982 season. Going into 1983, Bass was 29 years old and had a reputation as a AAAA player. He was the best (or tied with Tim Raines for the best) batter on his AAA teams for five years running, but got only inconsistent playing time in the major leagues, being yanked around for a total of 130 games over six seasons. It’s hard to know how he would have fared if he hadn’t been blocked by Rod Carew when he was a young man, or if he would have learned to hit major league pitching if he’s been given more of a chance to work at it. But at this point it was too late. A 29 year old first baseman who has yet to have major league success isn’t going to have a big league career. Traditionally, his future would have been as an organizational player, someone to fill out a AAA roster and give the actual prospects a warm body to play against. Maybe spend a few weeks in the big leagues, here and there, when someone gets injured. Bass decided to go to Japan instead. There were already some American players playing prominent roles in Japan when he went over, most notably the Lee brothers. Leron Lee had been a star for Lotte since 1977 and his brother Leon joined him a year later. Both were legitimate stars. So Bass wasn’t a trailblazer, but he was part of a generation of ball players who came to see playing in Japan has a viable career move, not a bizarre exception to the norm, but a part of it. The wave crested gradually, with more-and-more American players building substantial careers in Japan, and, increasingly, others using time in Japan (or Korea) as a springboard to return to MLB. Bass went over relatively early in this process, and never returned to American ball. I wonder if it was seen as a one-way ticket at the time? Japanese players did not come play in the US at the time, and the Japanese professional leagues were long viewed with suspicion on this side of the Pacific. That attitude has changed – in part because we’ve gotten better at understanding differences in context between different leagues, and in part because of the success in MLB of Japanese players – but it seems to have been the norm for a long time. I’m not sure about this, but there’s a chance that, in 1983, going to Japan was professional suicide, at least as far as MLB was concerned. Hanshin gave Bass more chances than any American team ever did. And they were rewarded handsomely for it. His performance in 1983 was in line with what he had been doing in AAA (so, it was good), but he took a big step forward the following year. He won his first of four consecutive batting titles, and would also win the triple crown in both 1985 (when he led the Tigers to a championship) and 1986. In his magical 1985 season he nearly broke Saduharu Oh’s single-season home run record, but in the last game of the season the Giants (then managed by Oh) intentionally walked him every time he came to bat. In Japan Bass was a superstar, posting on base percentages above 400 every year except his first. And except for an abbreviated 1988, his lowest slugging percentage while in Japan was 598. Let’s look at his performance relative to the league. In 1983 he finished 22nd in the league in on-base percentage (OBP) and second in slugging percentage (SLG), behind Reggie Smith. In 1984 he was fifth in OBP and second in SLG (behind Sadashi Yoshimura, although Bass had substantially more at bats than did Yoshimura). His great season, 1985, saw Bass finish first in both categories (as well as in hits and the triple crown stats). In his second triple crown season Bass again finished first in all three slash stats (BA/OBP/SLG), as well as hits, and second in runs scored. In 1987 he was third in OBP and third in SLG. We’ll get to 1988 in a minute. In 1985 the Central League as a whole hit 272/341/430. That’s a relatively high-offense league. But Bass was 41% better than average in OBP and 81% better in SLG. To do that in the 2024 American League you would need an OBP of 435 and a slugging percentage of 713. That’s not a bad match for what Aaron Judge did in 2024. Judge’s OBP was a little bit higher, but his slugging percentage was a little bit lower. So that’s how you should think about Randy Bass’ best year. He hit approximately as well (in context) as Aaron Judge c. 2024. And his 1986 was almost as good. Maybe Judge is a pretty good comp, at least offensively. (Defensively there’s a difference. Judge can play the outfield.) So much for the happy part of the story. This is where things get dark. In 1988 Bass’ eight-year-old son was diagnosed with brain cancer. He returned to the United States to get him treatment. The Tigers insisted that he left the team without permission and released him. (Bass also had a contractual provision that required Hanshin to pay for his family's healthcare, and he speculated that they may have thought that they could get out of paying for the cancer treatment if they released him.) In any event, he claimed that they had given him permission to leave the team and produced a recording proving it. The Tigers' new GM (he had been on the job for only 40 days), Shingo Furuya, a close friend of Bass’, came under intense criticism for how the team handled the situation. He met with Bass in LA to try to negotiate his return to the team (and perhaps to negotiate paying a smaller portion of the cost of the child’s treatment?), but Bass refused to leave his son. Shortly thereafter Furuya jumped to his death from the 8th floor of a hotel in Tokyo. Bass explained that leaving the team (even if done with the team’s blessing) is not what would have been expected in Japan. He said: "I don't think any of the Japanese players would have left. In Japan, the wife takes care of the children and takes care of the money; she does it all. The man's place is his job." Fortunately, Bass’ son survived, but the affair marked the end of his dad’s career. Bass claims that he was labeled a “troublemaker” and blacklisted from Japanese ball. He never did return to pro ball in the US, either. Post career, he ran a farm in Oklahoma, and was elected to the state senate, serving there until he ran up against a term limit and had to retire. Hall of Fame: Yes | Meikyukai: No The card is a 1986 Calbee. Probably the best card in the set at the time. Bass was coming off of a triple crown year and was about to win another one. Last edited by nat; 12-17-2024 at 03:32 PM. |

|

#2

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

Ricky Y |

|

#3

|

|||

|

|||

|

I forgot I had these (sorry for the fuzzy pictures). Just found them over at my parent's house.

My aunt in Japan had sent me some Calbee Japanese Cards back in the early 70's when I went back home and told her I collected baseball cards. I asked her to send me some when I returned back to the US. Well then she sent me these instead.  I have a few more of these that I opened that have other players. And I had one left that was not opened. Sean's blog had some cool info and photos about these. Although technically not cards, most of the photos have really nice action phots and some that are odd...haha. I was lucky enough when I was little to see Nagashima and Oh play while still with the Giants at Koraku-en stadium before the Tokyo Dome was built against the Hanshin Tigers. If I recall, the Giants won and Takahashi Kazumi started for the Giants. Ricky Y |

|

#4

|

||||

|

||||

|

Quote:

__________________

Collecting Federal League (1914-1915) H804 Victorian Trade Cards N48 & N508 Virginia Brights/Dixie/Sub Rosa NY Highlanders & Fed League Signatures ....and Japanese Menko Baseball Cards https://japanesemenkoarchive.blogspot.com/ |

|

#5

|

||||

|

||||

|

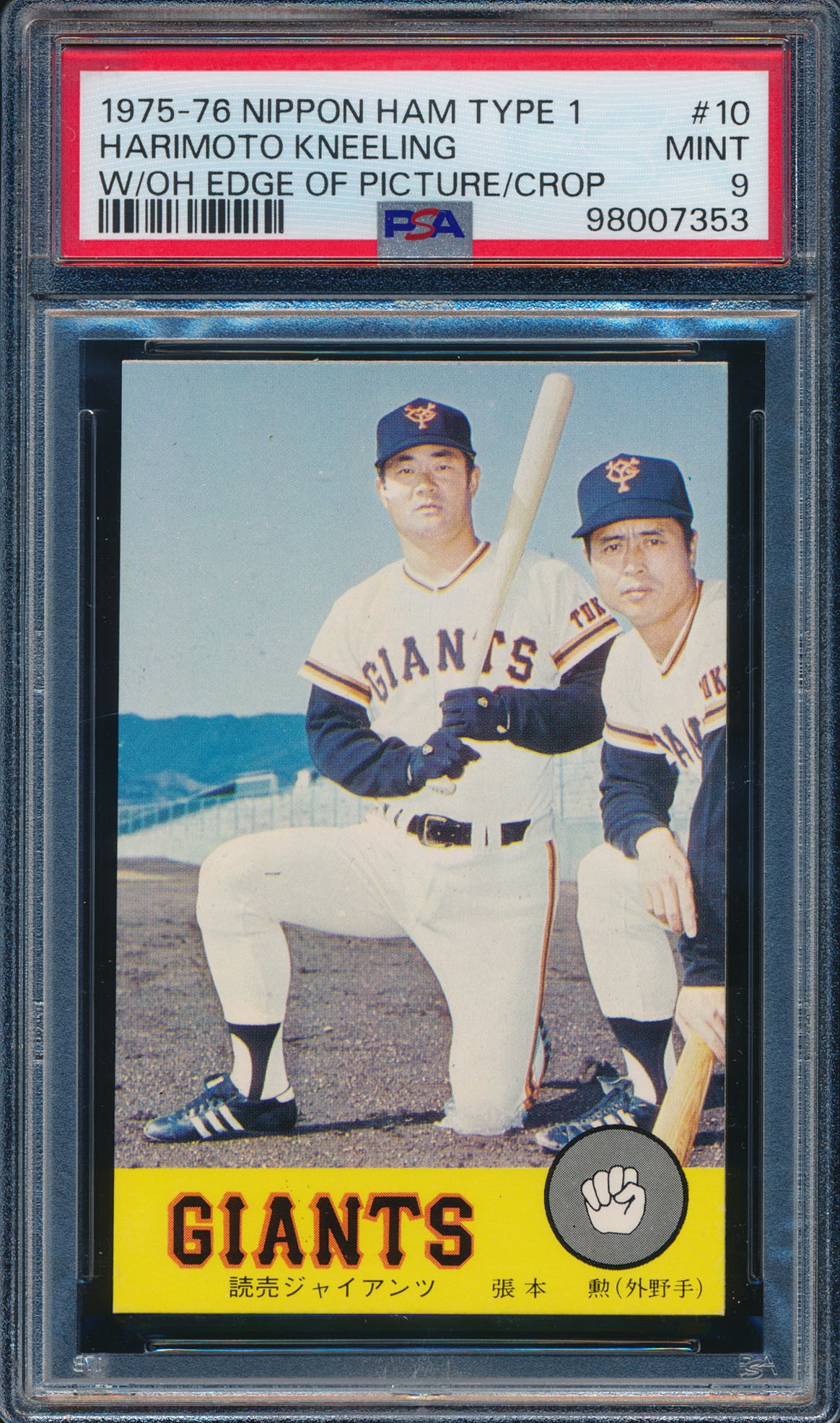

Anyone get anything fun in Prestige last night? I won this one:

Arguably the two greatest hitters in the league's history on one card? Yes, please. Ironic how the hit king and home run king of the Japanese majors are ethnic Korean and Chinese, respectively.

__________________

Read my blog; it will make all your dreams come true. https://adamstevenwarshaw.substack.com/ Or not... Last edited by Exhibitman; 04-13-2025 at 07:34 PM. |

|

#6

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

Ricky Y |

|

#7

|

||||

|

||||

|

Neat card Adam! Weird cropping decision though. It's like Oh just decided to photobomb Harimoto's card.

>>> The Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame has three new members. Ive been busy and havent had a chance to write up anything about them. Well go some distance towards correcting that today. Todays subjects are Ichiro Suzuki and Hitoki Iwase. They are both in the Meikyukai, so Ive written about them before. Click on their names for links to my previous posts. No new cards today, because Ive decided to retire my Meikyukai collection. Hence, the cards of them that I got for that collection are just going to be shifted over to the hall of fame binder. It was hard to muster the same sense of excitement for the Meikyukai as for the hall of fame. In part because some of the players are themselves less exciting. There are some great Meikyukai players who arent in the hall, but there are other guys who are less great, and I just find it hard to get worked up over the Japanese version of Mark Grace. Perhaps more importantly, all Meikyukai players are relatively recent guys, and I find the early days of Japanese ball much more interesting than the recent years. Ichiro is a lot more interesting than Iwase, so I am going to write about him today. In my last post about him I talked about the ways in which Japanese and American ball compare to each other, and what Ichiros success means for that comparison. Today Im going to talk about something different. Im going to talk about aesthetics. Let me tell you a story. Once upon a time, in 1961, the New York Yankees won the world series. Their starters had the following OPS+ scores: 209, 167, 153, 115, 113, 90, 79, 67. The guy they had batting leadoff, the guy who by definition gets the most at bats (assuming he doesnt miss any games, which he didnt) was Bobby Richardson, the guy with the 67 OPS+. They decided that their worst batter should be the one to get the most at bats, that they wanted to have a guy with a .295 on base percentage bat in front of 1961 Roger Maris. Because they had Maris and Mantle (and Berra and Ford and Howard) they won anyway, but this decision was, to put the point gently, suboptimal. But Richardson was a scrappy second baseman, and baseball tradition has it that scrappy second basemen bat leadoff. So thats how they did it. Not everyone bought into tradition. Earl Weaver liked to buck it. But it had a controlling influence in almost every MLB organization for decades. At some point someone, lets say, Bill James in the late 1970s although there were a few other voices in the wilderness, starting saying why dont we stop taking tradition for granted? The approach that James inaugurated gets called analytics and stats but James actually isnt very good at statistics and some of his uses of statistics dont, analytically-speaking, make much sense. But what he is very good at is asking questions and not assuming that he already knows the answers. The stuff about the math really isnt at the heart of the analytics movement; if I was to briefly summarize it, Id say that what analytics is about is investigating baseball scientifically. Math comes in because science is quantitative, and so math is the tool that lets you take observations and turn them into systematic knowledge. I am, and for a couple decades now have been, an ardent proponent of analytics in baseball. I love this sport, and I want to understand how it works. Its this scientific approach that has allowed me to do that. And one of the things that we have learned is that baseball tradition is often mistaken. Bobby Richardson, for example, was a terrible leadoff hitter. The 61 Yankees would have been better with Elston Howard up there, even though hes a plodding catcher and conventional wisdom says that plodding catchers will only clog up the base paths. But there have been costs. Let me tell you another story. This one is about another team that won the world series. The 1985 Royals didnt have Mantle or Maris, but they did have a pair of guys who slugged 30 HRs or more, one of whom (Brett) led the league in slugging percentage. The Royals had good power. But they also had a pair of regulars who stole more than 40 bases but hit fewer than 10 home runs (and Onix Concepcion, who did neither). And their catchers can be counted in the >10 HR club sort of out of courtesy only. Sundberg hit 10 exactly, and all of their backup catchers collectively contributed a total of one more. This meant that any given at bat is likely to be different than the one that came before it. Maybe Willie Wilson is going to hit a triple (he hit 21 of them that year). Or Lonnie Smith will hit a single and steal second. And then Brett will drive him in with a homer. The variety made the game exciting. But it didnt help the team win. Every team has an analytics department now, and those teams have figured out two things: that home runs are so valuable that its worth giving up lots of singles to get them, and that for most players there are specific things that they can do to their swing (getting the right launch angle and so on) to maximize their chances of hitting a home run. Given the state of the game (pitching trends, the elasticity of the ball, etc.) adapting players in the run-maximizing ways dictated by analytics is a winning strategy. Teams absolutely should do this! But it also imposes a kind of uniformity on the game. Seemingly everyone hits .230 with 20 HRs now, skinny shortstops included. Now, I do want to emphasize that teams (and players) are making the right decision here, this is better for your team than hitting .260 with 2 HRs. But it decreases the quality of the aesthetic experience for the fans. If you were watching the 1985 Royals there were lots of different things to anticipate, depending on who is up, and lots of different ways to be surprised. The current game features lots of players who are distinguishable not based on their skill sets, but on how good they are at employing the single set of skills that they share with seemingly everyone else. I dont want to exaggerate this. There is still some variation. Luis Arraez is a joy to watch. And a few superstars are either so talented (Ohtani, Judge) or have unique talents (Ronald Acuna, on a lower level Elly de la Cruz) that they spice up the modern game in something like the way that the contrast between Willie Wilson and George Brett used to. But the guys who are the exceptions to the rule today are mostly marginal players. Nick Madrigal. Esteury Ruiz got run out of the major leagues despite leading the league in stolen bases in 2023. You can and should appreciate Ichiro for his greatness. But there are other reasons to appreciate him too. I dont even know how you calculate a launch angle for that weird chopping swing of his. That he did it proves that if youre good enough you can be a viable major leaguer even if you dont hit 20 HRs a year. Its not so much that I miss Ichiros kind of player (Tony Gwynn, Rod Carew), although I miss that too, its more that I miss the variety between players. That hes of an extinct species meant that he gave the game a kind of variety that it needs. In one of his early Baseball Abstracts, Bill James says that traditional baseball fans resent sabermetrics, even though traditional baseball fans use numbers just as much as sabermetricians do, because the traditionalists use numbers to tell stories and sabermetrics uses numbers as numbers. And I think hes on to something here. If you run the models youll find that nine guys hitting .230 AVG / 20 HR has an advantage over the old kind of lineup. But .310/0, .288/6, .275/33, .220/27, etc. tells a better story. One reason to love Ichiro is that he lets you tell better stories |

|

#8

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

Ricky Y |

|

|

|

Similar Threads

Similar Threads

|

||||

| Thread | Thread Starter | Forum | Replies | Last Post |

| Japanese card help | conor912 | Net54baseball Vintage (WWII & Older) Baseball Cards & New Member Introductions | 5 | 02-10-2017 01:27 PM |

| Can You Get - BBM (Japanese) Singles | MartyFromCANADA | 1980 & Newer Sports Cards B/S/T | 4 | 07-23-2016 11:47 AM |

| Anyone have a 1930's Japanese Bat? | jerseygary | Net54baseball Sports (Primarily) Vintage Memorabilia Forum incl. Game Used | 13 | 02-13-2014 07:16 AM |

| Help with Japanese Baseball Bat ? | smokelessjoe | Net54baseball Sports (Primarily) Vintage Memorabilia Forum incl. Game Used | 5 | 03-02-2013 02:17 PM |

| Anyone read Japanese? | Archive | Net54baseball Vintage (WWII & Older) Baseball Cards & New Member Introductions | 14 | 05-03-2006 12:50 PM |